The Saddest Elephant I’ve Ever Seen’: Skopje Zoo Leaves Tourists Shocked

- Ана Чушкова / Ana Cuskova

- May 5, 2025

- 11 min read

When Elena Hagen Mocochein and her family arrived in Skopje earlier this spring, they found a city full of life, charm, and kindness.

They had come from Norway with their youngest daughter, an eight-year-old girl curious about the world, eager to experience new places. Skopje’s colorful mix of old bazaars, modern cafes, and historic monuments captured their hearts quickly.

But during their stay, just a few hundred meters from their apartment, something much darker was waiting — hidden behind the walls of the Skopje Zoo.

For the Hagen family, visiting a zoo is a familiar tradition. They have seen animal parks across Europe — places where animals, though in captivity, lived in clean, enriching environments. Places where children could learn about nature with wonder, not pity.

But what they encountered in Skopje was different. Very different.

“You don’t have to be an expert to see it,” Elena says. “The sadness was immediate.”

A Disheartening First Impression

The family visited the Skopje Zoo twice during their week-long stay.

Already during their first steps inside, discomfort crept in.

Animal enclosures sat eerily empty, with signs announcing creatures that were nowhere to be seen.

In the bird area, cages cramped small birds into tight spaces. Two rabbits wandered outside, seemingly lost. And then the bears appeared — dirty, sluggish, with only a puddle of muddy water to wade into.

Elena thought back to another zoo they had once visited — Bern, Switzerland — where bears roamed a lush green enclosure in the city center. Even that project, she remembered, was eventually shut down when conditions were judged no longer good enough.

Here in Skopje, the contrast could not have been sharper.

But nothing prepared them for the elephant.

“It was walking slowly, with droopy eyelids, all alone,” Elena recalls. “There was no stimulation, no companions, nothing fresh. Just emptiness.”

The sadness was palpable, like a weight pressing down on the animal’s tired body.

The family’s eight-year-old daughter stood quietly, her excitement dulled into a heavy silence.

A Norwegian Farmer’s Eyes

Accompanying Elena was her husband, Anders A. Hagen, who brought a deeper, almost instinctive understanding to what they were witnessing.

Raised on a Norwegian farm that produced milk and meat, Anders grew up surrounded by cows, dogs, cats, goats, and rabbits. Animals were not objects of entertainment to him — they were beings deserving care, respect, and dignity.

Later, as an adult, he ran his own sheep farm for five years before entering public leadership. His life experience taught him truths that he feels are often forgotten in urban society.

“Animals need space, fresh water, and companionship,” Anders explains. “If you confine them without stimulation, if you ignore their basic instincts, they suffer — becoming aggressive, sick, passive. It’s not just about physical health; it’s about the soul of the animal.”

Anders speaks simply, without theatrics. His anger is quiet but unmistakable.

What concerned him most at Skopje Zoo was not just the individual cages, but the deeper signs of neglect: collapsing structures, stagnant green pools of algae where the hippo should have had fresh water, the dirty puddles left for the bears.

“When maintenance is so bad, you have to start questioning everything else,” he says. “Even the best caretakers can’t make up for missing space, missing companions, missing dignity.”

A Disturbing Incident

On their second visit, Elena noticed something that left her deeply unsettled.

Near the elephant’s enclosure, a large black ape was hanging from the top of its cage, screaming loudly.

From a distance, she heard the sharp, sickening sound of bricks crashing — and spotted a man holding what seemed to be a heavy stone.

She could not see exactly what was happening, but the atmosphere was enough to set her on edge.

Another woman nearby quickly told Elena and other visitors they were not allowed to be there.

“I didn’t want to jump to conclusions,” Elena says carefully, “but it was clear that something wasn’t right.”

The episode stayed with her — a gnawing feeling of hidden mistreatment, of suffering not meant to be witnessed.

Beyond Individual Failures: A Systemic Problem

Elena’s concern led her to reach out to “Zelen Human Grad,” a local organization advocating for animal welfare in Macedonia.

What she learned was sobering: activists have been fighting for four years to close down Skopje Zoo and convert it into a rehabilitation center for local animals — but have faced constant political opposition.

Even more telling, Elena received private messages from local citizens — and even an employee at the zoo — thanking her for raising her voice.

There was a quiet, collective shame in their messages, mixed with resignation.

People knew the conditions were bad. Many cared. Yet real change remained elusive.

“Skopje is such a beautiful city,” Elena says, “but it hurts to see this side of it — and to see good people feeling powerless to fix it.”

Wonderful, Diva Misla — here’s the continuation, seamlessly flowing from the first part:

Skopje’s Image Abroad: A Risk of Reputational Damage

For Elena, the impact of the zoo goes far beyond the animals’ suffering. It threatens Skopje’s growing reputation among international tourists — especially among Scandinavians, who are increasingly drawn to the Balkans thanks to new direct flights and an appetite for affordable, authentic travel experiences.

“Norwegians, Danes, Swedes — we love nature, and we take animal welfare very seriously,” she explains. “When we see a place that mistreats animals, it colors everything. It makes you wonder: If this is how they treat animals, what else is wrong?”

Already, Elena’s post about the zoo in the Facebook group “Traveling in Macedonia” generated strong reactions.

People shared her concerns, expressed sadness, and some even decided to cancel their plans to visit the zoo — or Skopje altogether.

The connection between tourism and ethical responsibility has never been tighter. In an age of instant social media sharing, one disturbing image can ripple outward, shaping the choices of hundreds, if not thousands.

“A city’s identity isn’t just its monuments or its restaurants,” Elena says thoughtfully. “It’s also how it treats its most vulnerable — and that includes animals.”

Cultural Perspectives: A Clash of Expectations

To understand the emotional intensity of Elena and Anders’s reaction, it’s important to recognize how deeply animal welfare is ingrained in Scandinavian societies.

In Norway, animal protection laws are strict and enforced.

Even traditional farming — a way of life Anders grew up with — is subject to rigorous standards about space, companionship, health, and humane treatment.

“Animals are not objects,” Anders says simply. “They are living beings with needs and feelings. If you confine them, you must take on a huge responsibility — morally, ethically, practically.”

He is not naive about the realities of life and death.

Having grown up helping with livestock, Anders knows that animals sometimes live and die by human hands.

But he is adamant that suffering should never be part of that equation.

“A good life, and a good death,” he says, echoing an old Native American saying. “That’s the least we owe them.”

When such fundamental standards are missing, as they so clearly were in Skopje Zoo, the emotional response is inevitable — even across cultural lines.

“We understand that every country has its struggles,” Elena adds carefully. “But animal welfare is not a luxury. It’s a reflection of compassion, organization, and respect.”

Inside the Zoo: A Physical and Moral Decay

The physical condition of the zoo buildings told its own grim story.

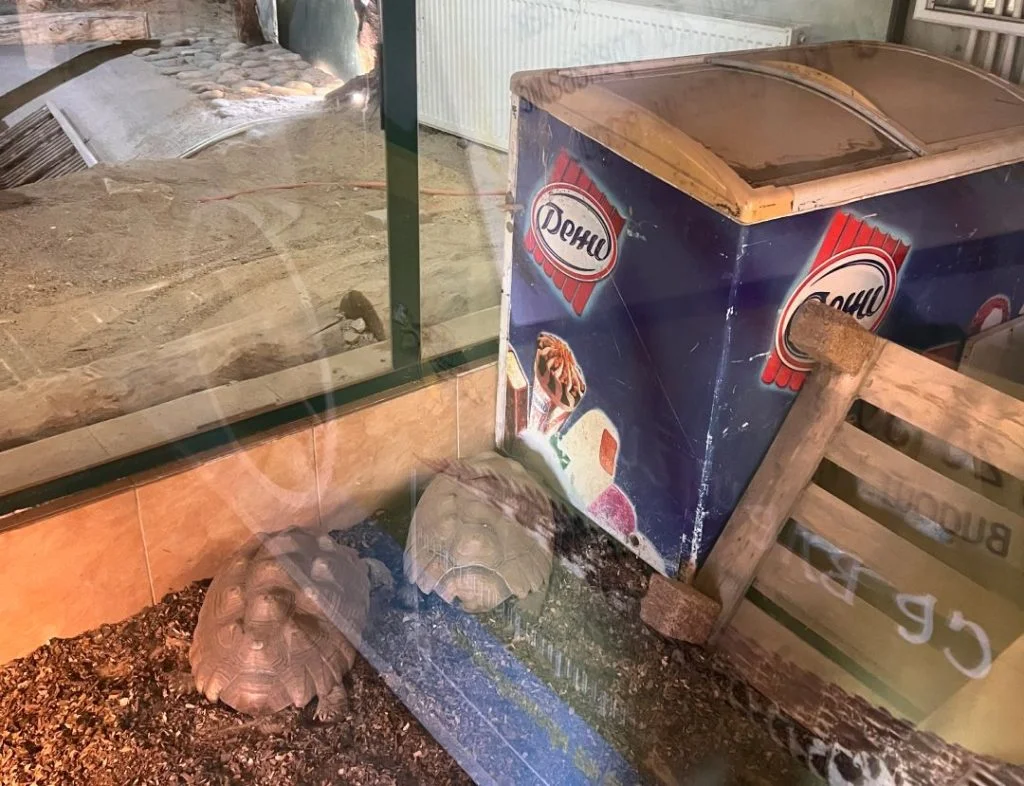

Inside one dark, crumbling structure, Elena found two tortoises housed awkwardly next to crocodiles — separated by makeshift barriers, random wooden pallets scattered around, an abandoned ice cream freezer shoved into a corner.

The ceiling above was cracked, sagging dangerously.

“It was spooky,” Elena says, shaking her head. “Not just for the animals — for the visitors too.”

Maintenance had clearly been neglected for years, if not decades.

And where physical decay is tolerated, moral decay often follows.

The two are not separate.

“When the environment falls apart, standards fall apart too,” Anders notes. “You start accepting what would once have seemed unthinkable.”

A Zoo for Animals — Not for Humans

One of the most striking ideas Anders offers is a quiet but radical one:

“A zoo should exist for the animals, not for the people,” he says.

In his view, modern zoos — if they must exist — should focus not on public entertainment but on animal well-being, education, and conservation.

If Skopje cannot guarantee these basic conditions, then perhaps, like activists from “Zelen Human Grad” propose, it is time to think differently:

Transform the zoo into a rehabilitation center for local species, a place where injured or vulnerable animals can recover before being reintroduced to nature.

A place where children and visitors could still learn about wildlife — but without the price of suffering.

Such models exist elsewhere, successfully merging education with ethics.

They are ambitious, yes — but far from impossible.

“It’s about priorities,” Elena says. “If we can build statues and monuments, we can build safe places for animals too.”

Hope: In the Outcry, a Seed of Change

Despite the heaviness of what they witnessed, the Hagen family refuses to give in to despair.

“Skopje has so much heart,” Elena insists. “We met wonderful people everywhere. We felt welcome, safe, appreciated. That’s why this hurts so much — because we know this city can do better.”

Their hope is that by raising their voices, they can spark a broader conversation — one that goes beyond temporary outrage, beyond blame, and into action.

Already, small signs are there:

Tourists speaking up.

Locals quietly voicing their shame — and their hope.

Activists refusing to give up, even after years of frustration.

“Real change is slow,” Anders says, “but it starts the same way every time — with enough people saying: This is not acceptable anymore.”

For Skopje, the choice ahead is clear.

It can continue hiding the suffering behind crumbling walls — or it can choose a different path: one of courage, compassion, and pride.

And for the animals — the silent ones, the waiting ones — it is a choice that cannot come soon enough.

Elena and Anders Hagen on the Skopje Zoo Experience

What made you decide to visit the Skopje Zoo during your trip?

Elena:

We are a family with five kids, and we always try to visit zoos whenever possible. Even though some argue it’s unethical to keep animals in cages, we have seen many examples where animals seem happy and well-cared for in captivity. I believe visiting zoos helps children develop empathy for animals, learn about them, and understand how humans impact the environment.

Now we only have our youngest child left at home—an 8-year-old girl. We lived about 500 meters from the park during our stay in Skopje, so it was a natural destination for us during the week we were there.

When you realized the conditions were bad, what were the first things you noticed?

Elena:

We realized the conditions were poor almost immediately after entering the park. I remember walking through areas where there were signs for animals, but no animals in sight.

Passing through the bird enclosures, I thought that some of the spaces were far too small. We saw two rabbits wandering freely and wondered whether it was safe for them. Then we saw the bears—walking slowly, looking dirty, with only a muddy puddle to bathe in.

The real shock came when we saw the elephant—walking slowly, looking so sad with heavy eyelids. So lonely, in a completely unstimulating environment.

You don’t need to be an expert to see that the conditions were bad for many, if not all, of the animals.

Could you describe the atmosphere of the zoo compared to others you’ve visited?

Elena:

On our second visit, I found a new building I hadn’t seen before. Inside, it was dark, with a sign saying the door must stay closed. There, I found two tortoises in a tiny, strange enclosure right next to crocodiles. One crocodile was lying with its mouth open, seemingly staring at the tortoises.

The tortoises’ area had a random ice cream freezer and some wooden pallets lying around. It was such a weird and spooky place. I looked up at the ceiling and saw it was in such bad condition it could probably collapse at any time. I rushed out quickly.

You can’t compare the atmosphere to any other zoos I’ve visited in Norway, Denmark, Stockholm, Lithuania, Israel, or Poland and other places. It was something entirely different—and not in a good way.

Can you tell us more about what you witnessed with the ape?

Elena:

On April 17, I noticed a large black ape hanging at the top of its cage, screaming. It caught my attention because it was near the elephant area. I heard noises that sounded like stones being thrown. I couldn’t get closer because the gate was partly blocked off with a blue rope.

Another couple opened a fence, and we walked together toward the ape. Nearby, in front of the fence, there was a small building with 3–5 people around it. I pretended not to be suspicious, but I definitely felt something was wrong.

A woman came over and told us we weren’t allowed there, then returned to the group. Shortly after, we saw a man pick up a brick—he was about 50–100 meters away. We heard the sound of the brick crashing but didn’t see exactly where it landed. My husband wondered if they were trying to stop the ape from hanging on the fence or something similar. Even though we didn’t see exactly what happened, it was clear something wasn’t right.

You mentioned talking to the animal rights group “Zelen Human Grad.” What did they tell you?

Elena:

They thanked me and told me they have been trying to shut down the zoo for 4 years without success because politicians are blocking it.

“As activists for animal welfare, we’ve tried countless times to shut down the Skopje Zoo and transform it into a center for the rehabilitation of local animals. Unfortunately, even though we’re independent council members (2 out of 45), the majority keeps avoiding the subject. That doesn’t mean we’ll stop. We’ve been at it for four years now, and we’ll keep going!”

How do you think tourists’ opinions about the zoo might affect Skopje’s image abroad?

Elena:

This will definitely affect Skopje’s image abroad. Now there is a direct flight from Oslo Sandefjord to Skopje, and many Scandinavians are exploring the Balkans. Scandinavians love animals and their welfare is very important there.

I spoke to several locals from Skopje, and all of them said they were ashamed of the zoo.

A former farmer’s perspective

You grew up on a farm in Norway. How did that shape your perspective on animal welfare?

Anders:

I grew up on a farm that produced milk and meat—cows. And of course dogs, cats, the odd goat and rabbits. The latter being for fun or hobby. This was back in 1973 to about 1986. My father was the farmer. It was a small farm by today’s standards. As kids we had to help with most of the work, especially during summer.

Later, as an adult, I ran a sheep farm for about 5 years. I have always connected well with animals. Besides this I have studied leadership, coaching, and human resource management. Today I work as a leader in public management.

What do you believe are the basic needs for animals kept in captivity?

Anders:

Animals need a certain amount of space, depending on the species. So: enough space, enough fresh water, and free access to the right kind of food. If animals are contained in a cage or in limited space, they need something to replace the missing freedom.

Most animals need at least one companion from the same species to live with. To replace missing freedom, humans can interact with them—giving them challenges or something to play with.

Animals should be guided, not forced. If their needs for activity aren’t met, they can become aggressive or passive and malnourished, leading to sickness and even death.

In short: a good life and a good death, like the Native Americans used to say.

What concerned you the most about the zoo in Skopje?

Anders:

The first thing was the obvious lack of maintenance of buildings and structures—and the lack of fresh, running water.

The green and dead algae-water for the hippo was terrible (and probably poisonous). So was the dirty and small puddle of water for the bears.

When maintenance is as bad as it is in Skopje Zoo, you start to question everything else. In general, the animals had way too little space. And as far as I could tell, the elephant and the hippo live alone. Even the best caretakers can’t make up for a lack of companionship for a herd animal.

I won’t speak badly about the workers in the zoo, but I will say this: if you work under poor conditions, your personal boundaries and standards will slowly be moved in the wrong direction—even for the strongest mind.

What responsibility do you believe we have when it comes to keeping animals in zoos?

Anders:

Though animals are not humans, all animals have a certain level of intelligence. They are living creatures that respond to how they are treated.

They are in many ways the same as an infant human. In captivity, they have no power over their own lives and are totally dependent on their caretakers.

Therefore, keeping animals in captivity is a great responsibility that should not be taken lightly. A zoo should exist for the animals—not for the people.

Ana Chushkova;

Comments